|

BARRIERS AND FACILITATORS OF COVID-19 PRACTICES AMONG CANADIAN SINGLE MOTHERS: A QUALITATIVE STUDY

|

Prevención de COVID-19, salud pública, barreras, facilitadores, Canadá

|

|

lpino2@uwo.ca

jmacderm@uwo.ca

lbrunto3@uwo.ca

sdoralp2@uwo.ca

(1) Department of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences, Faculty of Health Sciences, Western University, London, ON, Canada.

(2) Roth McFarlane Hand and Upper Limb Centre, St. Joseph’s Health Care London, London, ON Canada.

Autor de correspondencia:

Correo electrónico: lpino2@uwo.ca

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47187/cssn.Vol15.Iss2.350

|

|

|

|

|

Background: The COVID-19 pandemic introduced several new public health practices including mask wearing, social distancing, more frequent hand washing and disinfection of surfaces. Single mothers might have been uniquely impacted with the implementation of these preventive measures. Aim: The objectives of this qualitative study are to describe the experiences of Canadian single mothers with implementation of COVID-19 practices; and to identify barriers and facilitators to key public health behaviours, namely mask wearing, social distancing, hand washing, and disinfecting surfaces. Subject and methods: Twelve single mothers aged 18-51 years were recruited through purposeful sampling from social media platforms. Individual interviews were conducted using a semi-structured interview guide, transcribed verbatim, and qualitatively analyzed using thematic analysis and the approach of interpretative description. Results: The following challenges were noted for the public health behaviours. Volume of masks and keeping cloth masks clean were barriers to mask wearing. Loneliness and school closures were barriers to practicing social distancing. Being outside the home was a barrier to hand washing. Fatigue and time constraints were barriers to disinfecting surfaces. The following facilitators were highlighted by single mothers. Government mandates and public health messages were facilitators of mask wearing. Daily routine and technology were facilitators of social distancing. Types of hand soap was a facilitator for hand washing. Access to cleaning supplies and equipment were facilitators of disinfecting surfaces. Additionally, societal attitudes and stigma, pre-existing cultural and family norms, the impact of children’s age, and uncertainty related to changing knowledge about the virus were broad issues that affected all public health behaviours. Conclusion: COVID-19 practices were not straightforward to implement or adhere to single mothers. There was a broad array of barriers and facilitators that inform the need to build support systems. Further studies should account for generic issues and behaviour-specific barriers on assessing health-promoting interventions and implementing COVID-19 public health policies.

Keywords: COVID-19 practices, public health behaviours, single mothers, barriers, facilitators, mask wearing, social distancing, hand washing, disinfecting surfaces, Canada.

|

|

|

Introducción: La pandemia de COVID-19 introdujo varias prácticas de salud pública nuevas, como el uso de mascarillas, el distanciamiento social, el lavado de manos más frecuente y la desinfección de superficies. La aplicación de estas medidas preventivas podría haber afectado especialmente a las madres solteras. Objetivo: Los objetivos de este estudio cualitativo son describir las experiencias de las madres solteras canadienses con la aplicación de las prácticas COVID-19; e identificar las barreras y los facilitadores de los comportamientos clave de salud pública, el uso de mascarillas, el distanciamiento social, el lavado de manos y la desinfección de superficies. Sujetos y métodos: doce madres solteras de entre 18 y 51 años de edad fueron reclutadas mediante muestreo intencional a partir de plataformas de medios sociales. Se realizaron entrevistas individuales utilizando una guía de entrevista semiestructurada. Luego, se transcribieron textualmente y se analizaron cualitativamente la información utilizando el análisis temático y el enfoque de la descripción interpretativa. Resultados: Se observaron los siguientes problemas en los comportamientos de salud pública: el volumen de las mascarillas y mantener limpias las mascarillas de tela fueron barreras para el uso de mascarillas, la soledad y el cierre de los colegios fueron obstáculos para practicar el distanciamiento social, estar fuera de casa fue un obstáculo para lavarse las manos, el cansancio y la falta de tiempo fueron dificultades para desinfectar las superficies. Las madres solteras destacaron los siguientes facilitadores: los mandatos gubernamentales y los mensajes de salud pública facilitaron el uso de mascarillas, la rutina diaria y la tecnología permitieron el distanciamiento social, los tipos de jabón de manos proporcionaron el lavado de manos, el acceso a suministros y equipos de limpieza facilitó la desinfección de superficies. Además, las actitudes sociales y el estigma, las normas culturales y familiares preexistentes, el impacto de la edad de los niños y la incertidumbre relacionada con el cambio de conocimientos sobre el virus fueron cuestiones generales que afectaron a todos los comportamientos de salud pública. Conclusión: Las prácticas COVID-19 no fueron sencillas de aplicar ni de adherir para las madres solteras. Hubo una amplia gama de barreras y facilitadores que informan de la necesidad de crear sistemas de apoyo. Otros estudios deberían tener en cuenta las cuestiones genéricas y las barreras específicas del comportamiento a la hora de evaluar las intervenciones de promoción de la salud y aplicar las políticas de salud pública COVID-19.

Palabras clave: prevención de COVID-19, salud pública, barreras, facilitadores, Canadá.

|

|

|

The public health emergency of the COVID-19 pandemic produced worldwide mortality rates that necessitated a public health response. Governments rapidly mandated specific actions on personal protective behaviours to control pathogenic infection, including mask wearing, social distancing, more frequent hand washing and disinfection of surfaces [1-3]. By adopting these preventive measures, the overall goal was to reduce the virus transmission in the general population and to limit over-burden in hospital settings [2, 4, 5, 6]. However, there was low awareness of and willingness to implement these public health guidelines at the beginning of the pandemic [1]. According to the Angus Reid Institute, less than half (47%) of Canadians consistently followed public health guidelines in the sixth month of the COVID-19 pandemic, while approximately one-third (36%) of Canadians were inconsistent with the preventive measures. Finally, one in five Canadians (18%) do not implement COVID-19 practices (7).

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is spread through close contact from person to person causing COVID-19 infection [8]. Although the virus SARS-CoV-2 is primarily transmitted through respiratory droplets, contact with eyes, mouth, and nose, it can remain on frequently touched surfaces for up to 7 days [9, 10]. The mechanisms of transmission and seriousness of overall infection determined the importance of public health behaviours. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend mask wearing helps to prevent the transmission of respiratory droplets when people talk, cough, and sneeze [11]. Furthermore, a systematic review of personal protective behaviours during COVID-19 confirmed that masking had the potential to minimize the risk of virus infection [8].

The CDC also recommended implementing social distancing, also known as physical distancing, aims to reduce physical interaction and lower the spread of COVID-19 [12]. Social distancing is the practice of keeping a distance of 2m (metres) or 6 feet of open space between people [13, 14]. A systematic review supports that at least one metre, and if feasible two metres, is required to help prevent transmission of SARS-CoV-2 [8]. Lessons from China, Spain, and Italy indicated that social distancing lessened the spread of the virus [14]. The most frequently policy that focused on social distancing was stay-at-home orders, in which people experienced changes in daily routines and work-related practices. This had direct and indirect effects on job loss and child-care arrangements [15].

The CDC also recommended more frequent hand washing as a preventive strategy to slow the spread of SARS CoV-2 virus [16]. Hand hygiene is considered a significant preventive measure that can reduce viral transmission by 55% [6]. To be effective hand washing must be done properly, for at least 20 seconds using water and soap, or an alcohol-based sanitizer [17-19]. During the pandemic, the CDC recommended using water and soap for hand washing, and to use hand sanitizers when these were not available [16]. This recommendation reflects that soap is effective against the virus, and potentially less harmful to skin and the environment.

The recommendation of the CDC to increase the frequency of disinfecting surfaces with soap or detergent products to remove contaminants and decrease the risk of infection was made as SARS-CoV-2 can survive on plastics, metals, and surgical masks from 10 hours to 7 days [20]. Evidence indicated that the largest knowledge gap in disinfecting surfaces was safe preparation of disinfectant solutions [21]. There are also risks associated with high use of disinfecting products. For example, bleach products were reported as the source of 62% of poisoning exposure followed by hand sanitizers 36.7% during the COVID-19 pandemic [22]. Despite limited knowledge on safe preparation of disinfectants, surface disinfection was high to prevent COVID-19 during the first lockdown in March 2020 [19, 9].

Gender and other demographic factors can affect adherence to health behaviours. In children, girls are more willing to engage in hygiene-related practices than boys [5]. The same pattern continues in adulthood that self-protective behaviours are higher in women than men [23, 19, 18, 24, 25]. However, women-headed households have encountered unique challenges related to COVID-19 public health guidelines [13]. For instance, restrictions on social gatherings included closures of public facilities such as schools, childcares, and workplaces, which in turn affected single mothers as they were obligated to take time off work to fulfill family and childcare responsibilities within the home [26]. This resulted in women filling unpaid roles at home as many did not have the option to work from home or make special childcare arrangements [27]. To inform and improve public health policy, it is paramount to understand the experiences of single mothers that hinder or facilitate COVID-19 practices. As such, the purpose of this article is to highlight how single mothers adapt to mask wearing, social distancing, more frequent hand washing and disinfection of surfaces as they try to stay healthy, while meeting family responsibilities since they do not have another person helping in the home, and help outside the home may be restricted by public health rules.

|

|

|

2.1.- RECRUITMENT OF PARTICIPANTS

Study procedures were reviewed and approved by the Western University Health Science Research Ethics Board (HSREB) on May 17, 2021, Project ID 118854. Study participants were recruited through purposeful sampling. The official Facebook and Twitter social media platforms of the Hand and Upper Limb Centre (HULC) were used to recruit participants through a poster. Inclusion criteria included individuals who: (1) self-identified as single mothers and have dependent children living in the home; (2) spoke fluent English; (3) were over the age of 18; (4) were able to provide informed consent; and (5) resided in Canada. Participants were provided with the letter of information and signed consent through a Western Qualtrics online form prior to the one-on-one interviews. Formal written consent was obtained from participants, and any identifying information about participants were changed to pseudonyms. Due to the COVID-19 restrictions for in-person activities, we created a unique Western Corporate Zoom link for participants according to the time that worked best for each of them.

2.2.-DATA COLLECTION

One-on-one interviews were conducted by the first author, using a semi-structured interview guide to gain a better understanding of the personal protective behaviours that have been recommended for preventing COVID-19: mask wearing, social distancing, hand washing, and disinfecting surfaces. Each interview lasted approximately 60 minutes and was conducted via a Western Corporate Zoom video call. The interviews were audio recorded using an encrypted device and transcribed verbatim. Pseudonyms were assigned to keep participants’ identity anonymous.

2.3.- DATA ANALYSIS

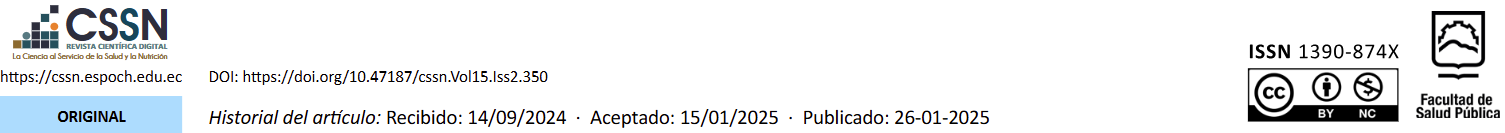

The Arise Framework was developed that uses an analytic guide, which consisted of a set of questions with the goal to orient data organization in a theory-driven content analysis (Fig 1). The initial analysis sample yielded twelve interviews. Thereafter, a further criterion was not considered because the point of data saturation was reached with the initial sample criterion as new information was not emerging after the twelve interviews [29].

Figure 1: The Arise Framework for qualitative data analysis

Figure source: Created by Dr. Lisbeth Pino

The concepts of credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability were used to establish trustworthiness in this qualitative study [30]. Credibility was maintained throughout the interview with frequent member checking following participants’ responses to ensure accurate interpretations. Transferability consisted of detailed descriptions of participants. Dependability was achieved through reflexivity as a coherence process between data collection and data analysis. Finally, confirmability involved creating and reviewing analytic memos, in which participants’ contextual factors were documented.

|

|

|

Twelve Canadian single mothers, aged 18-51, participated in one-on-one interviews. Participants were Canadians who self-identified as a single mother. Nine single mothers had school age children and three single mothers had children of daycare age. Seven single mothers were unemployed and had one dependent child. Five single mothers were employed and had two dependent children. Out of the twelve single mothers, two identify their nationality as Korean, two as Indian, and the remainder as Canadian (Table 1).

Table 1. Description of study participants

|

Pseudonyms

|

Age |

Number of children |

Occupation status |

Nationality |

|

Caitlin |

39

|

1 school age daughter |

Unemployed |

Canada |

|

Shona |

45 |

2 school age daughter and son |

Employed |

India |

|

Jillian |

29 |

1 son in daycare |

Unemployed |

Canada |

|

Mikaela |

18 |

1 daughter in daycare |

Unemployed |

Canada |

|

Jasmine |

41 |

2 school age daughter and son |

Unemployed |

Korea |

|

Anne-Marie |

51 |

1 school age son |

Unemployed |

Korea |

|

Jolene |

40 |

2 school age sons |

Employed |

India |

|

Jami |

37 |

2 sons in daycare |

Unemployed |

Canada |

|

Lisa |

29 |

1 school age daughter |

Unemployed |

Canada |

|

Becca |

45 |

1 school age daughter |

Employed |

Canada |

|

Shelly |

38 |

2 school age daughters |

Employed |

Canada |

|

Alice |

33 |

1 school age son |

Employed |

Canada |

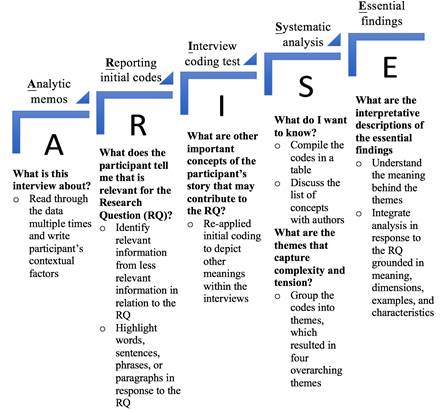

Regarding the experiences of single mothers in implementing COVID-19 practices, the following barriers and facilitators emerged for mask wearing, social distancing, hand washing, and disinfecting surfaces. The key findings of our study are summarized in Fig 2. The yellow box highlights the broad issues affecting all public-health behaviours: societal attitudes and stigma, pre-existing cultural and family norms, children’s age, and uncertainty about the virus.

Figure 2. Barriers and facilitators of COVID-19 practices

Mask wearing

At the beginning of the pandemic, single mothers bought masks in large quantities as it was hard to get the right fit. One participant highlighted, “When I go in a store. It is like falling off… I have to buy quite a few until I found some that fit very well, and those I don’t mind anymore. I want something that fits well” (Lisa). Single mothers experienced that their children got used to face masks quickly. One participant elaborated, “I was so impressed for these children and how well they adapted to these changes. She did not complain once” (Caitlin). Mask wearing became part of the daily routine of going out. To facilitate this, mothers reported using a box besides the door helped as a visual reminder to grab a reusable cloth mask. One participant added, “Just in case we forget our masks… We have 30 masks” (Jolene). In addition, single mothers considered mask wearing to be a respectful protective behaviour. By doing it, they showed to care for themselves and others.

Barriers of mask wearing. Mask wearing was a difficult adjustment as faces have different sizes, and one’s nose and mouth being covered might not be comfortable. One participant stressed, “I would find it sometimes like panicking with masks with the cloth ones because it is hard to breathe” (Shelly). This personal protective behaviour has had a greater impact on some mothers more than others. For example, mask wearing might lead to health reactions, especially during long periods of time. One participant explained:

More at work, I got acne for wearing the mask. That wasn’t fun to deal with. It can get painful. I use disposal masks. I do not have acne now, but I notice that restart going back to work. So, that is kind of a nice thing of not working. I ended that getting a medication from my doctor (Jillian).

Single mothers suggested that there is a need to reframe the mask wearing protocol for people who work eight hours a day or work in certain conditions. One participant said, “I am really scared to go back to work this summer… wearing a mask all day in the heat” (Caitlin). Regarding cloth masks, the barrier was keeping them clean. When masks were used, single mothers and their children did not wear them again, which was the main rationale behind stock piling many masks in a box. One participant claimed, “It can be very easy not wash them every day. I think if you want to get the most effectiveness, you should probably have a 50 of them, and constantly kind of washing them” (Lisa). Time constraints prevented single mothers from washing reusable masks on a regular basis.

Facilitators of mask wearing. Mask wearing was a mandated public health protocol in Canada during the COVID-19 pandemic. One participant stated, “The rule was put forward by the province. Otherwise if there is no rule, wearing a mask in the public would look different” (Shona). The government rule was the biggest facilitator for everyone to wear a mask in public places. Public health messages also promoted the adoption of this health behaviour. One participant provided an example of an effective message from her original home country of India: “a mask cost 10 rupee, but if you get COVID, you have to wear the oxygen [that] is going to be very expensive. So, you choose whether you want the mask or whether you want the oxygen” (Jolene). Although there were no specific examples of effective public health messages in Canada, participants pointed out that the practice of wearing a mask on a regular basis reinforced collective efforts.

Social distancing

Social distancing measures included stay-at-home orders besides keeping distance of six feet apart between people. This resulted in going out for essentials only, for example, to the grocery store. One participant emphasized, “We don’t go anywhere except of going for groceries” (Alice). Additionally, single mothers considered the importance of children’s outdoor activities due to the isolation with no school and no extra curricular activities. One participant mentioned, “I think going to the playground is so important. We do it almost every day, really” (Caitlin). However, mothers with young children struggled to teach them to maintain their distance: “I can’t really teach him. I tried to teach him through this entire pandemic to give space and stay in a certain amount away. It seems that is not getting in” (Jami). Single mothers noted that distancing was an ongoing struggle. Although they promoted the rules, their children enjoyed being near other children. While for single mothers, social engagements were limited. One participant noted, “I do not invite people home for social gatherings during the weekends what I used to do before” (Shona). To implement social distancing, single mothers referred to their defining social bubbles. In other words, social bubbles were defined in terms of the most critical with loved ones and few friends whom they associated with regularly.

Barriers of social distancing. Single mothers described social distancing as lonely and emotional that lacked connection with other people. Single mothers expressed the needs of their children. One participant stressed, “We still miss our friends. He asks me, mom, can we do this? Can we go somewhere?” (Anne-Marie). Although single mothers were unhappy about social distancing measures, they were able to follow the rule. However, the struggle was to constantly reinforce social distancing among their children by explaining they cannot do what they want because of the government rule. Children aged 3-7 years had difficulties with physical boundaries. One participant said, “When kids see their friends, it becomes very difficult for them not to be close” (Jolene). Children can be very physical in terms of hugging and touching other children, and it is challenging for mothers to teach them social distancing. One participant stated, “He is always at people’s face, giving people hugs, and trying to kiss people. So, I really struggle with him” (Jami). In fact, physical presence was important not only for children, but also for mothers. One participant illustrated how social distancing felt, “You just want companionship. We just want to be around their friends. It doesn’t feel great because you want to hug your friend, being closer. Don’t look at them that they are a pile of germs” (Jillian). As a sole parent, companionship provided them mental stability. While the lack of social connections underlined vulnerabilities for single mothers during a pandemic.

Another challenge for single mothers was the transition from in-person school to online home-school. Since children were home, some single mothers were off work due to lack of internal supports within the home. One participant commented, “The biggest one is that the schools been closed. Obviously as a single mom trying to work, having my daughter not in school is really tough, and still is. Last year, I was off work for seven months” (Caitlin). Single mothers juggled to adapt changes in family responsibilities and recognized the value of school hours between 9:00 am to 3:00 pm in relation to their jobs. Mothers did not feel as competent as teachers in providing online learning support. One participant expressed:

To be honest, what I find frustrating it is that depends on the day when the teacher isn’t even there. Maybe, she has an appointment. For whatever reason, she takes the day off or a lot of times the work is assigned. Then the kids have to do outside of the virtual class hours. In my opinion, they waste a lot of this virtual class doing lessons … they are not really getting those lessons (Lisa).

Children were used to receiving in-person lessons from their teachers. In turn, mothers found that online home-school was not the same learning-structure for their children.

Facilitators of social distancing. Social distancing had slowly become an everyday practice even though single mothers did not believe the pandemic would last for more than a year. One participant noted, “It has become so much of a habit. At the start, it was so weird to have to keep distance for our loved ones. I think it just becomes so second nature now. It becomes a part that we are all thinking about it. It becomes ingrained in your habits” (Shelly). Social distancing was repeated regularly in which this practice enhanced an unconscious pattern of behaviour. Single mothers had learned to keep distance as much as possible: “I know how to keep it, but I always thinking about my kids” (Shona). Single mothers used technology such as Zoom and FaceTime to communicate with their family and friends. One participant explained, “I can get everything that bothers me, get my frustrations, talk to somebody about your irritations on whatever is going on at that point” (Alice). The social component was rooted in mothers’ emotional needs that they need others to do well and stay well.

Hand washing

Single mothers preferred hand sanitizers and wipes rather than implementing hand washing behaviours. One participant commented, “We carry out those sanitizers and wipes with us when we go out… My daughter is used to it” (Caitlin). Sanitizers and wipes were always available for mother and child in a box near the main entrance to the house. Hand washing was considered for dirty hands. One participant emphasized, “We may be implemented once or twice a day. If they are really dirty, I get them to wash” (Jami). During the COVID-19 pandemic, hand washing was emphasized as a health behaviour to develop a strong habit. One participant explained, “It was also an eye opening to us that how many people don’t really wash their hands. They have to be told. Many people kind of push that away” (Mikaela).

Barriers of hand washing. Being outside the home was challenging for single mothers and their children because of the inability to find public facilities for hand hygiene. One participant mentioned, “The most frustrating things is that public places are open, but there are no public washrooms. There was no place to wash your hands, that is kind of gross” (Caitlin). This was also challenging for single mothers with little children, especially regarding proper hand washing. One participant added, “My youngest wants to play with the water forever, and taking him away is a major thing. I struggle there. My oldest is fine” (Jami).

Facilitators of hand washing. Single mothers highlighted that hand soap made hand washing a more positive experience. For example, a soap that smells nice could encourage hand washing for 20 seconds. Using different types of hand soap was the main facilitator for success in achieving hand washing behaviours as single mothers did not have to work as hard to implement the behaviour in older children as they did in younger children. One participant explained, “It is probably because my kids are the age that they are. The thing with younger kids, it would be that you have to stay on top a lot more” (Shelly). Children’s age was a factor influencing their ability to practice hand washing on their own. One participant agreed by saying, “I think that is easier with my daughter because being 10. She understands things a lot more. I think it would be more challenging for a 3-years old to wash their hands and wear a mask” (Lisa).

Disinfecting surfaces

Surfaces were disinfected more frequently at the beginning of the pandemic. Single mothers cleaned handles, steering wheels, door knobs, cars, and groceries, using chemical products and wipes. One participant stated, “I have a spray, which I spray on my shoes. I make sure that we all put our shoes outside the house” (Shona). However, surfaces were disinfected less over time due to changes in knowledge about the virus. Single mothers explained that extra cleaning is not a mandatory behaviour to prevent COVID-19. As such, cleaning remained the same as before. One participant commented:

I clean and I disinfect, but I don’t do more than I did before. I disinfect my entire bathroom when I clean it and my kitchen. I wash the floors with bacteria killing products that I use. I do enough as it is. I do my bathroom once a week. Probably I do my kitchen probably every two days [and] the house three days a week (Jami).

Overall, there was not an increased in house cleaning because participants observed that disinfecting did not have an impact on preventing COVID-19.

Barriers of disinfecting surfaces. The primary barrier that single mothers experienced in disinfecting surfaces was lack of energy due to childcare responsibilities. Motherhood without external supports was time-consuming. Daily struggles to perform all parenting duties alone, in some cases with decreased supports than prior to the pandemic was a major concern of single mothers. Every step for them was a struggle, and it was related to parenting alone during COVID-19. One participant highlighted, “Just giving the amount of time I have, cleaning takes probably four to five hours in a week… It tires me out because we don’t go out too much, but it is still. That takes a very long time” (Jolene). When single mothers saw the need to clean and disinfect, it was still challenging because of time constraints. One participant remarked, “I think it is hard because you just can’t do it once a week. I don’t really think that is effective. You probably have to do it every day” (Lisa). Single mothers devoted most of their time to childcare as their primary and most important family responsibility.

Facilitators of disinfecting surfaces. Disinfecting wipes were the supplies that facilitated the process to clean surfaces. One participant mentioned, “One of the things they keep saying is that it removes 99.9% of bacteria” (Jolene). However, single mothers understood that disinfecting surfaces is not a mandatory behaviour to prevent COVID-19. Additionally, access to disinfectants facilitate house cleaning. One participant stated, “I think it is the same as just having the mask thing, knowing where they are. I mean accessibility” (Jillian). Besides chemical supplies, single mothers also found it useful to have multiple cleaning tools such as a vacuum, broom, and cloths for wiping floors. These tools were used once a week.

Societal attitudes, cultural norms, children’s age, and uncertainty of the virus influenced all COVID-19 practices

Regarding mask wearing and social distancing measures, there was conflict between social stigma and medical issues. In fact, health conditions hindered the ability to wear a mask for a few mothers. One participant examined:

We face a lot of rude comments. A lot of ignorance towards people who can’t wear one. We did try, but it made our medical condition so much worse. I cannot wear neither disposal nor cloth masks. We keep our distance from people. It is very frustrating to go out in public now with all these masks, especially because being one of the few that we can’t wear one. It is very frustrating (Mikaela).

There was also lot of pressure on mothers who cannot wear a mask to find employment as mask wearing is mandatory in public places. Being a sole parent in the home without sources of income jeopardizes the opportunity to provide for the family.

In terms of hand washing behaviours, cultural norms were visible. A mother of Korean descent explained that washing hands was part of her culture, while in Canada, it was observed that it is not natural:

When we eat together if I ask my son to wash his hands because we are going to eat supper now, and then [Canadian friend] is really surprise for that. She said, oh that is a really good habit. You guys always do that? Yes, Korean people likes to do that, not every Korean, but usually for the family who has kids. I do not think this is a special habit here (Anne-Marie).

The ability to recognize the need to wash hands more often was a positive attitude from mothers in implementing this preventive measure. However, age is an important factor influencing whether a child engages in this behaviour on their own. One participant noted, “I think that having a three-year-old. He is in his own little world, which is normal. I am here, wash your hands” (Jillian). Single mothers felt responsible to teach their children this practice: it was an ongoing awareness to be fully present to stay healthy.

For disinfecting surfaces, uncertainty was a recurrent theme due to evolving knowledge about the virus. One participant said, “At some point it came out that COVID doesn’t transmit as much on surfaces as it does in the air. We have read some articles that wasn’t a necessary behaviour anymore. So, we really relaxed on that front” (Shelly). While outside the home, uncertainty was manifested in attitudes of fear in bringing something into the house. One participant remarked, “That ongoing fear in your head that why if I have something in my hands. It is something you can feel it. It is that fear not so much for myself. Although fear for myself too because you just never know with COVID” (Shelly).

|

|

|

This study highlights that a sample of single mothers engaged in voluntary personal protective behaviours supported by public health advice to slow the spread of COVID-19. Although there was high adherence to public health guidelines, single mothers experienced a broad array of barriers. A study reported that the major stressors of the COVID-19 pandemic were quarantine duration, fear, unclear information, inadequate supplies, and financial constraints [31]. The shutdown of public facilities compromised mothers’ employment, school closures, and family/social supports were no longer available. Mothers felt lonely, which was directly related to parenting “more” alone during COVID-19.

The most important personal protective behaviours for Canadian single mothers were mask wearing and social distancing measures. Their experiences illustrated that mask wearing and social distancing bears the burden of protecting self and others. A study found that mask wearing and social distancing behaviours required less physical effort compared to hand washing and disinfecting surfaces [32]. This may be an important contributor to the findings of the current study as a result of the increased responsibilities single mothers faced during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Mask wearing behaviours led single mothers to acquire big quantities of cloth masks. Our findings related to the high volume of masks in single mothers agrees with a narrative review of mask wearing that reported a high level of adherence among women [26]. Motivation is a central predictor to behaviour change, mothers’ motivation in our study was driven by protecting others by wearing a mask [33]. The only women who did not use masks in our study did so for medical reasons and experienced stigma as a result. The impact of societal pressures was evident through discriminatory comments in public spheres for single mothers who were medically exempted from mask wearing. General public health campaigns had been a channel to promote mask wearing behaviours. There is evidence that some people experienced barriers to mask wearing due to certain medical conditions [32]; however, public health messages did not address this challenge. Research has demonstrated that when preventive messages are focused on a prosocial framework, the messaging is more effective [2, 4]. As such, prosocial emotional messages should aim for a compassionate approach towards people who are unable to wear a mask. This might increase the likelihood that all members of society respect one another.

Social distancing measures had a negative effect on single mothers’ emotional well-being. Loneliness was present among many single mothers while dealing with unemployment and daily stressors of home and family responsibilities. This was congruent with another qualitative study, which found that social distancing resulted in the loss of social interaction, income, and daily routine during the pandemic [31]. Outside the home, the playground was a recurrent place for mothers and their children to visit. However, their children had a difficult time keeping their distance from other children. Evidence showed that social distancing among children is not effective as it is for adults [5]. This explains the constant struggle single mothers experience in trying to teach their children to keep a distance of two feet apart. Single mothers were responsible not only for their children’s entertainment, but also for their children’s home-schooling. Decisions to cancel in-person schools impacted children, leaving them without access to educational centres and extracurricular activities, therefore, a substantial burden of supervising children with online education and homework fell upon mothers’ shoulders. Caregiving burdens increased, while mothers’ well-being decreased. This was consistent with another study that found the added responsibility associated with online learning increased parental levels of stress, worry, and social isolation [27]. Single mothers grieved the loss of external supports in isolation.

Hand washing was challenging to implement outside the home as washrooms in public facilities were closed even if other parts of the service were opened. As such, hand sanitizers were more frequently used among single mothers and children. Before COVID-19, routine preventative hand washing was not being a habit, instead it was implemented for dirty hands only. This finding agrees with a study in Vietnam that reports low adherence to hand washing practices [24]. Hand washing can become a lifelong habit, but the process of forming that habit should start in childhood [3]. However, our study revealed that single mothers experienced more difficulties in teaching their young children hand hygiene habits compared to mothers with older children. In Wuhan China, for example, it was observed that more than half of primary students had improper hand washing during February 2020 [3]. Basic hand washing education should be encouraged, as people adopted better hand washing practices after a demonstration, improving performance by six times better performance [17]. Proper hand washing technique and frequency are needed especially before meals, after sneezing and coughing, and when coming home.

Disinfecting surfaces was a predominant strategy used in the early stage of the pandemic only. A similar pattern was found among US adults who highly engaged in household cleaning and disinfection [21]. Our findings reveal that this behaviour gradually lessened as mothers learned that COVID-19 is transmitted more frequently through respiratory droplets rather than surfaces. Although it was beneficial to have access to cleaning supplies and equipment, single mothers expressed that fatigue and time constraints were impediments to disinfecting schedules, which was related to parenting alone during an ongoing pandemic. This is supported by research that demonstrated low levels of adherence were reported if disinfecting surfaces required a large amount of effort [9].

Strengths and limitations

This study was conducted amid the COVID-19 pandemic (May - June 2021) so that single mothers had sufficient time to implement and adapt to public health recommendations. We achieved diversity of different types of single mothers, including different ethnicity, ages, employment status and number/age of children. There are limitations that should be noted. Our focus on specific public-health directives did not include all recommendations e.g. avoidance of touching mouth, nose, and eyes, and that while personal factors related to the mother may have influenced these behaviours we did not focus on this aspect. Furthermore, the role of culture and societal values was considered in our sampling and became a latent theme in some of the answers; however, this study was not designed to look at cultural differences, rather it was a reflection of a North American context.

|

|

|

Single mothers encountered challenges during the pandemic related to societal attitudes and stigma, pre-existing cultural and family norms, the impact of children’s age, and uncertainty related to changing knowledge about the virus. These broad issues affected all public health behaviours. In addition, some barriers were noted for adherence to recommended public health behaviours. Volume of masks and keeping cloth masks clean were reported as barriers of mask wearing. Loneliness and school closures were reported barriers to social distancing barriers. Being outside the home was a barrier to hand washing; and fatigue and time constraints were barriers to disinfecting surfaces. Despite the willingness to follow COVID-19 protocols, behaviour change was not straightforward because of these challenges and being a single parent without employment and social supports during the pandemic. Finally, some facilitators were highlighted in implementing personal protective behaviours. Government mandates and public health messages were facilitators of mask wearing. Daily routine and technology were facilitators of social distancing. Types of hand soap was a facilitator of hand washing and access to cleaning supplies and equipment were facilitators to disinfecting surfaces. Further studies should focus on assessing health-promoting interventions that consider generic issues and behaviour-specific barriers that address the extra difficulties that single mothers experience in implementing pandemic-related public health policies.

|

|

|

1. Zhou M, Long P, Kong N, Campy KS. Characterizing Wuhan residents’ mask-wearing intention at early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Patient Education and Counseling. 2021; 104(8): 1868–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2020.12.020

2. Coroiu A, Moran C, Campbell T, Geller AC. Barriers and facilitators of adherence to social distancing recommendations during COVID-19 among a large international sample of adults. PLOS ONE. 2020; 15(10): e0239795. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239795

3. Głąbska D, Skolmowska D, Guzek D. Population-based study of the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on hand hygiene behaviors—Polish adolescents’ COVID-19 Experience (PLACE-19) study. Sustainability. 2020; 12(12): 4930. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajt.16300

4. Dehghani S, Pooladi A, Nouri B, Valiee S. Barriers and facilitators of adherence to the COVID-19 prevention guidelines: A qualitative study. Caspian Journal of Health Research. 2021; 6(1): 9–20. https://doi.org/10.32598/CJHR.6.1.343.1

5. Chen X, Ran L, Liu Q, Hu Q, Du X, Tan X. Hand hygiene, mask-wearing behaviors and its associated factors during the COVID-19 epidemic: A cross-sectional study among primary school students in Wuhan, China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(8): 2893. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17082893

6. Haque M. Handwashing in averting infectious diseases: Relevance to COVID-19. J Popl Ther Clin Pharmacol. 2020; 27(SP1): e37–52. https://doi.org/10.15586/jptcp.v27SP1.711

7. Angus Reid Institute. COVID-19 Compliance: One-in-five Canadians Making Little to no Effort to Stop Coronavirus Spread (August 2020) [Internet]. [cited 22 April 22]. Available from: https://angusreid.org/covid-compliance/

8. Chu DK, Akl EA, Duda S, Solo K, Yaacoub S, Schünemann HJ, et al. Physical distancing, face masks, and eye protection to prevent person-to-person transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet. 2020; 395(10242): 1973–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31142-9

9. Gharpure R, Miller GF, Hunter CM, Schnall AH, Kunz J, Garcia-Williams AG. Safe use and storage of cleaners, disinfectants, and hand sanitizers: Knowledge, attitudes, and practices among U.S. Adults during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2021; 104(2): 496–501. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.20-1119

10. Sun Z, Ostrikov K (Ken). Future antiviral surfaces: Lessons from COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainable Materials and Technologies. 2020; 25: e00203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.susmat.2020.e00203

11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Use and Care of Masks (December 2021) [Internet]. [cited 22 April 22]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/cloth-face-cover-guidance.html

12. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidance and Tips for Tribal Community Life During COVID-19 (December 2021) [Internet]. [cited 22 April 22]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/tribal/social-distancing.html

13. Behar-Zusman V, Chavez JV, Gattamorta K. Developing a measure of the impact of COVID-19 social distancing on household conflict and cohesion. Family Process. 2020; 59(3): 1045–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12579

14. Qian M, Jiang J. COVID-19 and social distancing. J Public Health (Berl). 2020; 30: 259–261. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-020-01321-z

15. Ares G, Bove I, Vidal L, Brunet G, Fuletti D, Arroyo Á, et al. The experience of social distancing for families with children and adolescents during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic in Uruguay: Difficulties and opportunities. Children and Youth Services Review. 2021; 121: 105906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105906

16. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. When and How to Wash Your Hands (December 2021) [Internet]. [cited 22 April 22]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/handwashing/when-how-handwashing.html

17. Yigzaw N, Ayalew G, Alemu Y, Tesfaye B, Demilew D. Observational study on hand washing practice during COVID-19 pandemic among bank visitors in Gondar Town, Northwest Ethiopia. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment. 2021; 0(0): 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2021.1943592

18. Al-Wutayd O, Mansour AE, Aldosary AH, Hamdan HZ, Al-Batanony MA. Handwashing knowledge, attitudes, and practices during the COVID-19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia: A non-representative cross-sectional study. Scientific Reports. 2021; 11(1): 16769. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-96393-6

19. Brown LG, Hoover ER, Barrett CE, Vanden Esschert KL, Collier SA, Garcia-Williams AG. Handwashing and disinfection precautions taken by U.S. adults to prevent coronavirus disease 2019, Spring 2020. BMC Res Notes. 2020; 13(1): 550. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-020-05398-3

20. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cleaning Your Facility. (December 2021) [Internet]. [cited 22 April 22]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/disinfecting-building-facility.html

21. Gharpure R, Hunter CM, Schnall AH, Barrett CE, Kirby AE, Kunz J, et al. Knowledge and practices regarding safe household cleaning and disinfection for COVID-19 prevention — United States, May 2020. American Journal of Transplantation. 2020; 20(10): 2946–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajt.16300

22. Samara F, Badran R, Dalibalta S. Are disinfectants for the prevention and control of COVID-19 safe? Health Security. 2020; 18(6): 496–8. https://doi.org/10.1089/hs.2020.0104

23. Dindarloo K, Aghamolaei T, Ghanbarnejad A, Turki H, Hoseinvandtabar S, Pasalari H, et al. Pattern of disinfectants use and their adverse effects on the consumers after COVID-19 outbreak. J Environ Health Sci Engineer. 2020; 18(2): 1301–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40201-020-00548-y

24. Huong LTT, Hoang LT, Tuyet-Hanh TT, Anh NQ, Huong NT, Cuong DM, et al. Reported handwashing practices of Vietnamese people during the COVID-19 pandemic and associated factors: a 2020 online survey. AIMS Public Health. 2020; 7(3): 650–63. https://doi.org/10.3934/publichealth.2020051

25. Pedersen MJ, Favero N. Social Distancing during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Who Are the Present and Future Noncompliers? Public Administration Review. 2020; 80(5): 805–814. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13240

26. Seale H, Dyer CEF, Abdi I, Rahman KM, Sun Y, Qureshi MO, et al. Improving the impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions during COVID-19: examining the factors that influence engagement and the impact on individuals. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2020; 20(1): 607. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-020-05340-9

27. Ribeiro FS, Braun Janzen T, Passarini L, Vanzella P. Exploring changes in musical behaviors of caregivers and children in social distancing during the COVID-19 outbreak. Front Psychol. 2021; 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.633499

28. Viner RM, Russell SJ, Croker H, Packer J, Ward J, Stansfield C, et al. School closure and management practices during coronavirus outbreaks including COVID-19: a rapid systematic review. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health. 2020; 4(5): 397–404. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30095-X

29. Francis JJ, Johnston M, Robertson C, Glidewell L, Entwistle V, Eccles MP, et al. What is an adequate sample size? Operationalising data saturation for theory-based interview studies. Psychology & Health. 2010; 25(10): 1229–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870440903194015

30. Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park CA: Sage Publishing;1985.

31. Williams SN, Armitage CJ, Tampe T, Dienes K. Public perceptions and experiences of social distancing and social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic: a UK-based focus group study. BMJ Open. 2020; 10(7): e039334. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039334

32. Benham JL, Lang R, Burns KK, MacKean G, Léveillé T, McCormack B, et al. Attitudes, current behaviours and barriers to public health measures that reduce COVID-19 transmission: A qualitative study to inform public health messaging. PLOS ONE. 2021; 16(2): e0246941. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0246941

33. Schunk DH, DiBenedetto MK. Motivation and social cognitive theory. Contemporary Educational Psychology. 2020; 60: 101832. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2019.101832.